Building a Byte-Pair Encoding Tokenizer From Scratch

I have procrastinated long enough in building a tokenizer from scratch. Although I’ve gone through Sebastian Raschka’s Build an LLM from Scratch book long ago (it’s a fantastic resource to begin with), I’ve never truly built every part of an LLM stack ground up. I stumbled upon Stanford’s CS336 recently and it’s such a fantastic resource - got completely hooked on to a course after sooo long. The best part of the course so far? Forced myself to write code without using AI after maybe ~5 years or so (yes I had access to GPT3 back in 2021) and it is incredibly fulfilling to have written a parallelized BPE tokenizer.

The following contents of the blog are mostly what I learnt while building the tokenizer portion of assignment 1 in CS336 (which is merely just the first 10 pages of the whole 50 page assignment PDF...).

Being true to the CS336 course curriculum, I just ran the tests that were provided with the assignment to check for correctness and didn’t compare my implementation with anything that’s already out there. All the code that I’ve written here so far is just me (and Claude as my TA for high level programming related questions). If at all you’d like to do the assignments on your own - please stop reading right here and revisit some other time :)

More than the tokenization stuff, I’m going to highlight things I newly learnt along the way - from multiprocessing in Python to using Scalene for profiling my code and optimizing my tokenizer to run over ~2.7x faster.

If you want to learn more about tokenizers and deep dive, also consider this resource from sensei Andrej Karpathy - Let’s build the GPT Tokenizer.

A Quick Take On Tokenization

Tokenization is a process where words are broken down into smaller pieces, and ultimately tokens or the numerical representation of these words so that the computer can understand and work with them to generate text. Given how all of AI is just fancy math and stats in the background - we can get it to work mainly only with numbers, which is why we need to convert them to this form to begin with.

A vocabulary of a tokenizer is essentially the number of possible tokens we want the tokenizer to learn and use to convert words to int and bytes and back and forth.

Vocab size = number of possible tokens

Here are the different types of tokenization we could potentially consider:

Character-based

Convert every char in a word or a token to unicode.

char → unicode

Cons: large vocabulary; characters can be quite rare

Byte-based

Another approach would be to just use 256 bytes and convert all chars to bytes and back and forth with the tokenizer.

Pros: small vocab size (just the 256 bytes)

Cons: very bad compression ratio - we’d have to use a significant number of tokens to represent our content

Word Tokens

One other approach we could do is to use regex and split strings to get the words separated and assign integers to each spelled word.

Cons: unseen words / rare words have no meaning for the model and they will break at runtime.

BPE (Byte Pair Encoding)

The star of the show, aka Byte Pair Encoding, is one of the efficient algorithms still in use today. It tackles most of the cons in the previously discussed methods by doing something called sub-word tokenization, where a word is split into smaller meaningful subtext or subword for tokenization purposes. This helps to have a good compression ratio, while also handling the problem of unseen or unknown words for LLMs.

The algorithm essentially repeatedly merges the most frequently appearing pair of bytes.

Note: Byte tokenization often yields more tokens than word-level tokenization because of this subword behavior.

BPE tokenization is a midpoint between word-based approaches and “byte/char”-style approaches. The tradeoff is a larger vocab since we merge most frequent pairs and add them to the vocabulary.

BPE Training

Initial vocab: We’ll start with just the classic 256 bytes like in the UTF-8 encoding.

BPE tokenization goal: ensure semantic differences don’t require adding new “unnecessary” tokens. Originally, words were split by space before subword tokenization. But of late, the following regex pattern from the GPT-2 tokenizer implementation is commonly used:

PAT = r"""'(?:[sdmt]|ll|ve|re)| ?\p{L}+| ?\p{N}+| ?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+|\s+(?!\S)|\s+"""

NOTE: The original implementation in GPT-2 tokenizer used

regex.findall()which incredibly slowed down performance. We should useregex.finditer()to avoid storing pre-tokenized text.Compute BPE merges: Essentially, all we’d have to do is:

Count every pair of bytes

Identify the highest-frequency pair

Merge into a new token

example:

("a", "b") → "ab"

Then, we add the merged token to the vocabulary, while also storing the merges separately (which we’ll need later during encoding).

Note about special tokens: We also need to add the special tokens to the vocab. Importantly, we don’t split them into substrings at all - they have to be retained as-is to be useful. For example, the <|endoftext|> token helps a model learn when to stop generating.

The rudimentary BPE algorithm is quite simple and the previous text is enough to probably code it out given input and output requirement specifications.

Regardless, here’s how we’d do the major part:

Pre-tokenize corpus (using the regex pattern we previously discussed)

Convert to UTF-8 bytes

Compute frequency of all pre-tokens

From the computed pre-tokens, find frequency of all byte pairs

Merge the most frequent byte pair together as a new token (i.e., a new integer)

Add to vocabulary (which starts with 256 bytes of UTF-8 + special tokens)

Update the previous byte pairs where this new max frequency pair is occurring

Repeat steps 4-7 until we learn a vocabulary of intended size (many models used to use 32K vocab)

The More Interesting Bits

The first bottleneck we’d hit is pre-tokenization. Regex is actually quite slow and having a huge corpus makes it even worse. The best way to handle this would be to parallelize the pre-tokenization as we could merge the frequency counts later.

In order to do multiprocessing in Python, we could use, well, the multiprocessing library and create X number of pools that execute in parallel. This in itself is a huge optimization that can help us save a lot of time by running these processes in parallel.

Quick example on how to do parallel processing in Python:

import os

from multiprocessing import Pool

def multiply(x: int) -> int:

# Example: multiply by 10

return x * 10

def main():

workers = os.cpu_count() * 2 # "processes" = cpu_count * 2

data = list(range(1, 21)) # 1..20

with Pool(processes=workers) as pool:

results = pool.map(multiply, data)

print("workers:", workers)

print("input: ", data)

print("output: ", results)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

This would spin up twice as many processes as your CPU count and multiply each number from 1 to 20 by 10. Although this is very poor use of multiprocessing (pool creation overhead would be higher than the process itself), we could use this to parallelize our pre-tokenization process.

Given we’re parallelizing our pre-tokenization, the best way to do it would be to chunk the training corpus split by special tokens. For instance, with <|endoftext|>, we could have independent n number of chunks that can be worked on independently per document without crossing boundaries for the byte pairs.

Here’s a function that returns a dict[bytes, int] where the bytes are of the pre-tokens we extracted from regex:

def get_freq_counts(

input_path: str | os.PathLike,

chunk_start: int,

chunk_end: int,

special_tokens: list[str]

) -> dict[bytes, int]:

with open(input_path, "rb") as f:

f.seek(chunk_start)

chunk = f.read(chunk_end - chunk_start)

text = chunk.decode("utf-8")

special_token_pattern = "|".join([re.escape(token) for token in special_tokens])

docs = re.split(special_token_pattern, text)

PAT = r"""'(?:[sdmt]|ll|ve|re)| ?\p{L}+| ?\p{N}+| ?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+|\s+(?!\S)|\s+"""

freq = defaultdict(int)

for doc in docs:

for tok in re.finditer(PAT, doc):

tok = tok.group()

freq[tuple(list(tok.encode("utf-8")))] += 1

return freq

We could parallelize the calls to this function by:

word_freqs = defaultdict(int)

num_chunks = os.cpu_count() * 2

split_special_token = b'<|endoftext|>'

with open(input_path, "rb") as f:

chunks = find_chunk_boundaries(f, num_chunks, split_special_token)

args = [(input_path, start, end, special_tokens) for start, end in zip(chunks, chunks[1:])]

with Pool() as pool:

res = pool.starmap(get_freq_counts, args)

for freq in res:

for word, counts in freq.items():

word_freqs[word] += counts

Once we have this multiprocessing step, we have already gotten rid of the most inefficient part of a tokenizer. The second big bottleneck comes from the merge step which unfortunately would have to be linear for the way the algorithm works, as we keep track of the order of merges later for encoding and decoding these tokens.

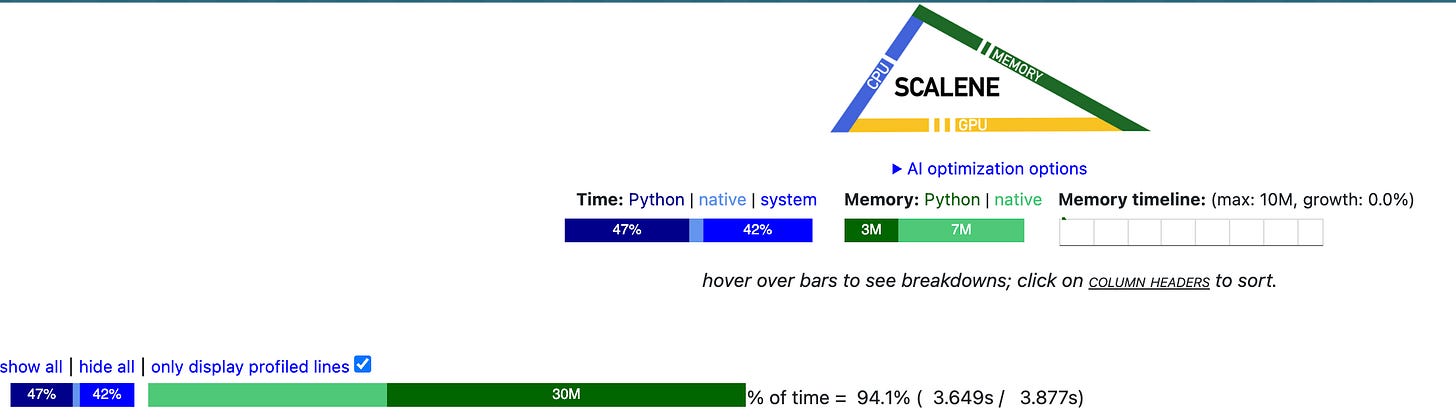

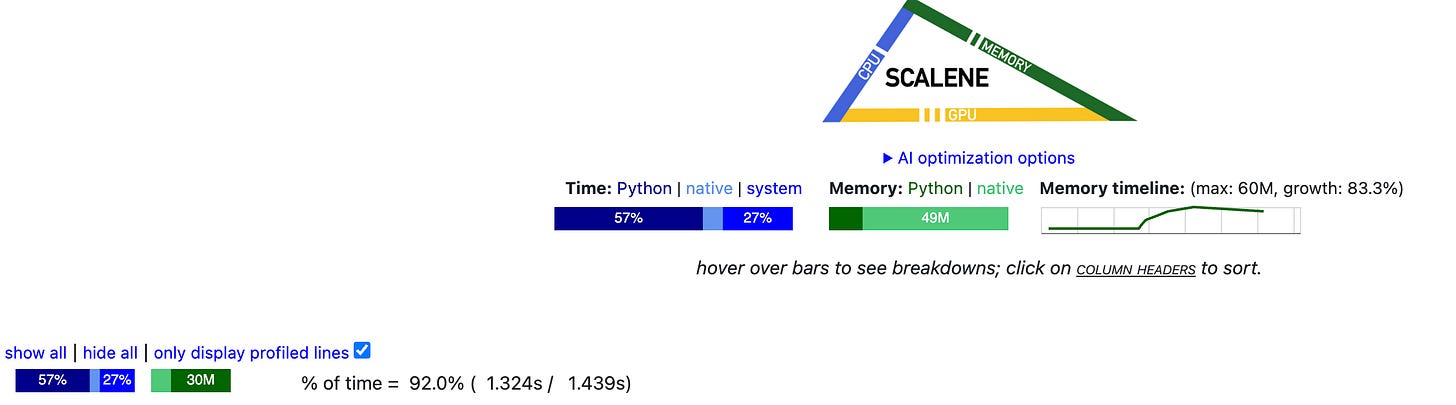

Here’s where profiling comes into play! Scalene is an awesome profiling tool that can help you diagnose the slowest part of your code.

On profiling my implementation, I found out that a majority portion of my merge logic was slow because I was checking for merges in all of the original pre-tokens, which sometimes could be millions and billions of tokens themselves. It quickly shoots up and the tokenizer would be largely inefficient.

Being also nudged by the assignment instructions, I decided to now keep track in a dictionary that knew which byte pair was present in which words (as a set), and additionally also keep track of keys that are newly merged or modified in a list. Adding these two data structures helped me cache and update only the required portion and voila, there was a ~2.7x speedup in the implementation.

Following are snippets from the code profiling on training the BPE tokenizer on the validation set of the TinyStories-GPT4 dataset:

The TinyStories 10K vocab tokenizer training was done in under 1.5 min, and the OpenWebText 32K vocab tokenizer took ~4.5 hours to complete.

Using the trained tokenizer:

For encoding and decoding, the logic is quite straightforward and uses the pieces we previously discussed.

Encoding:

In order to make sure that we treat our special tokens correctly, we should first split the text by special tokens using regex. Following that, the steps are as follows:

If it’s a special token, insert the token ID from vocab

Else, pre-tokenize using the previously discussed GPT-2 regex pattern

Now, we just need to sequentially apply the merges learned during training repeatedly until no more merges are left to tokenize these pre-tokens

The major efficiency-related concern here is that if we were to do the brute-force approach, we’d be looping through all the merges repeatedly, and that quickly gets very expensive. The two simplest high-ROI optimizations I found, again with Scalene, were:

A merge priority dictionary where the key is the

(ch1, ch2)byte pair from the merges, and the value is the priority itself.For tokenizing large corpora, I found that reducing the number of lookups to the vocab during merge could be achieved by having another dictionary that just returns the merged token ID for every possible merge key. (This could also be a potential waste of memory when not used for large corpora.)

self.merge_priority_by_id = {

(self.vocab_byte_to_int[ch1], self.vocab_byte_to_int[ch2]): i

for i, (ch1, ch2) in enumerate(self.merges)

}

self.merge_result = {

(self.vocab_byte_to_int[ch1], self.vocab_byte_to_int[ch2]): self.vocab_byte_to_int[ch1 + ch2]

for ch1, ch2 in self.merges

}

One additional optimization I could think of—which I haven’t completed yet—is using a min heap for the priority and somehow reusing the possible byte pair scans that we do. This should significantly reduce compute as well. But I’m pretty sure this isn’t a straightforward fix to handle edge cases (I may be wrong on this front though).

On testing the compression ratio performance of the tokenizers:

32K Vocab OpenWebText Tokenizer on OpenWebText: 4.37

10K Vocab TinyStories Tokenizer on TinyStories: 4.12

10K Vocab TinyStories Tokenizer on OpenWebText: 3.17

From which I believe they’re doing quite well on the compression front.

Decoding:

Decoding is very straightforward. Essentially, we just have to join all the bytes together after converting int token IDs to bytes and use UTF-8 decode to put the text back together. One caveat is to make sure we use errors='replace' in byte decoding so that malformed bytes are taken care of by Python.

def decode(self, ids: list[int]) -> str:

decoded_bytes = b"".join(self.vocab[id] for id in ids)

return decoded_bytes.decode("utf-8", errors='replace')The training code and a trained vocabulary and merge file for TinyStories-GPT4 (10K vocab) and OpenWebText (32K vocab) can be found in this repo: light-tokenizer.

If you’ve read this far, thank you for reading!